xkcd, 2007.

I gave this presentation on February 4, 2008 at the eTech Ohio Conference under the title “Can We Use Wikipedia Appropriately?”

To begin with the basics, Wikipedia is an online encyclopedia that anyone can write and edit. It’s an ambitious project, and one with both positive and negative aspects. Ideally, Wikipedia will help democratize education, providing the same information for free to everyone with an internet connection. In the worst case, this will be misinformation, and the site will miseducate.

The vast majority of Wikipedia articles can actually be changed by anyone. If you go to any article, you’ll find an “edit this page” link at the top, allowing you to do exactly that. Because anyone can add to or change Wikipedia entries, there’s no guarentee that information will be accurate. For the very same reason, though, anyone who finds a mistake, lie, or even grammatical error in an article can correct in themselves, making it easy to improve articles. I’m convinced that the vast majority of information on Wikipedia is accurate, and that it deserves some role in educational institutions. I also believe, however, that this role should be carefully considered and limited, and that educators should understand the process by which Wikipedia functions, not only the articles that result from it.

One reason I think that educators should learn about Wikipedia is that students already are. Bill Tancer, a researcher for Hitwise who studies consumer behavior online, notes that many of the popular search terms that bring users to Wikipedia from sites like Google “bear a close resemblance to elementary school homework and research projects.”

During the month of February, which is also Black History month, three of the top 20 terms sending traffic to Wikipedia were for prominent black historical figures, while two other searches were likely motivated by Presidents Day. In fact, changing timeframes to any other month during the school year reveals a similar result.

Bill Tancer, “Look Who’s Using Wikipedia,”

Time, March 1, 2007.

If students are already using Wikipedia as a resource, it’s important that teachers understand it. You might find more to like than you expect. I’ll tell you a bit about three attractive features of Wikipedia, though I’ll mention some negative aspects along the way too. These will be citations, comprehensiveness, and the site’s history and discussion tools.

The topic of Wikipedia and education has already received some press, though it’s mostly dealt with higher education. The most discussed event was a decision by the history department at Middlebury College to ban citing of Wikipedia in student papers. What’s interesting to me about this decision is that it actually reflects a consensus of educators and Wikipedians that the site is best used as a starting place for research rather than as a student’s only source. The following quotation is from Wikipedia cofounder Jimmy Wales.

The advice I would give to students is be careful how you use Wikipedia. It really isn’t a trusted source. It really is edited real-time and it could be full of mistakes.… I think it basically should be fine in schools… to add a footnote saying I did a lot of my preliminary research in Wikipedia, just to acknowledge where you got a lot of knowledge. But in terms of citing specific facts, you really should go to the sources and look it up there, because that’s what you’re supposed to be doing. The encyclopedia is supposed to give you the broad overview, not be a primary research tool…. I would say the same thing about Brittanica, by the way.

Jimmy Wales, net@nite 13,

February 13, 2007.

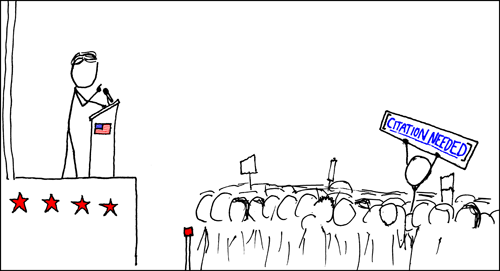

Fortunately, Wikipedia can be very helpful to those looking to find other sources on a subject. Articles generally have superscript links to endnotes interspersed throughout their text. There are many articles on the site without citations, but they are viewed by regular users as unpolished and in need of substantiation, while numerous citations are a hallmark of a good article. Today’s featured article on the site, about a polar bear named Knut, has 41 citations in a few pages of text. (Because Wikipedia is always changing, this might be different when you visit the article; you can see it as I did.) Because it’s about recent events, these citations all include links to stories in traditional news media, but articles also frequently cite books, academic journals, and other authoritative sources. The role of citations is so central on Wikipedia that they have come to be identified with the site.

Randall Munroe, “Wikipedian Protester,”

xkcd, 2007.

Another attractive feature of Wikipedia is its comprehensiveness. The English language site has over two million articles, many of them quite long and thorough. There have been a few studies comparing the coverage and accuract of Wikipedia to traditionally edited commercial encyclopedias.

The historian Roy Rosenzweig published an article on Wikipedia a year and a half ago in which he compared the site to both Encarta and American National Biography Online.

To find 4 entries with errors in 25 biographies may seem a source for concern, but in fact it is exceptionally difficult to get every fact correct in reference works.… I checked 10 Encarta biographies for figures that also appear in Wikipedia, and in the commercial product I found at least 3 biographies with factual mistakes. Even the carefully edited American National Biography Online, whose biographies are written by experts, contains at least one factual error in the 25 entries I examined closely, the date of Nobel Prize winner I. I. Rabi’s doctoral degree—a date that Wikipedia gets right.…

Wikipedia, then, beats Encarta but not American National Biography Online in coverage and roughly matches Encarta in accuracy.

Roy Rosenzweig, “Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past,”

The Journal of American History, June 2006.

American National Biography Online is a subscription service generally used by professional historians rather than students, so the performance of the free Wikipedia is pretty impressive. Also, Wikipedia generally improves in both accuracy and coverage as more people use and edit it, so Rosenzweig’s conclusions might be even more positive were he writing now.

The journal Nature, one of the two most prestigious in the sciences, published a similar comparison of Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica’s web edition. They printed out copies of articles on the same topics from both websites without the source identified and sent them to experts. Their conclusions may be surprising:

Among 42 entries tested, the difference in accuracy was not particularly great: the average science entry in Wikipedia contained around four inaccuracies; Britannica, about three.…

Nature’s investigation suggests that Britannica’s advantage may not be great, at least when it comes to science entries. In the study, entries were chosen from the websites of Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica on a broad range of scientific disciplines and sent to a relevant expert for peer review. Each reviewer examined the entry on a single subject from the two encyclopaedias; they were not told which article came from which encyclopaedia.…

Only eight serious errors, such as misinterpretations of important concepts, were detected in the pairs of articles reviewed, four from each encyclopaedia. But reviewers also found many factual errors, omissions or misleading statements: 162 and 123 in Wikipedia and Britannica, respectively.

Jim Giles, “Internet encyclopaedias go head to head,”

Nature, December 15, 2005.

Note that the Nature article is a couple of years old. I haven’t been able to find more recent such studies of the English language Wikipedia, though the magazine Stern did just publish an article on the German one under the heading “Wie gut ist Wikipedia?”

Stern said the Wikipedia’s average rating was 1.7 on a scale where 1 is best and 6 is worst. The Brockhaus rated 2.7 on the same measure.

The articles were assessed for accuracy, completeness, how up to date they were and how easy they were to read.

In 43 matches [out of 50], the Wikipedia article was judged the winner.

“Magazine hails German Wikipedia as better than encyclopaedia,”

Deutsche Presse-Agentur, December 5, 2007.

The third attractive feature of Wikipedia is actually two features, the discussion and history pages. Every article has a set of links along the top. One of these links to the history of an article, which takes the form of a list of all the revisions that have been made. Because Wikipedia articles generally improve as more people edit them, simply looking at the number or frequency of these revisions can tell you something about the article. It's also possible, though, to click on the date of any one of these revisions and see how the article looked at that point in time. One can trace the development of an article all the way back to its original form, which is often only a sentence or two.

Another of these tabs at the top of an article to that article’s discussion page, also called the talk page. Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg, researchers at the IBM Visual Communication Lab, describe it this way.

The talk page is where the writers for an article hash out their differences, plan future edits, and come to agreement about tricky rhetorical points. This kind of debate doubtless happens in the New York Times and Britannica as well, but behind the scenes. Wikipedia readers can see it all, and understand how choices were made.

Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg, “The Hive Mind Ain’t What It Used To Be,”

Edge, 2006.

The talk page is a great way to learn more about how an article is put together and decide how much to trust it. One can easily imagine a writer and editor at the New York Times arguing about whether an individual sentence or idea should appear in an article, but most of us never get to see this process in action. Wikipedia allows us to peel back the veil and see how our reference source is produced.

The article on Knut that I mentioned earlier is a “featured article,” selected because it’s particularly good. The range of article quality on Wikipedia is enormous, so now we’ll now look at an article that, while not exactly bad, isn’t up to the same standard. Garrett Morgan was an African American inventor who lived in Cleveland and is best known for his work on gas masks and traffic signals. His article on Wikipedia, unlike many websites run by museums and schools, does not claim that Morgan was the first to invent either the gas mask or the traffic signal. (The article has probably changed since I wrote this; you can see it as I did.) Most of the discussion page deals with these questions of priority, and specifically with whether to cite a website that provides apparently accurate descriptions of earlier inventions similar to Morgan’s, but appears to be motivated by racism. This is the sort of discussion from which one can learn a great deal, both about history and about how people use and learn from history.

The Garrett Morgan article also demonstrates something completely different: that the quality of writing on Wikipedia is often very poor. This is partly because of “writing by committee” and partly because many contributors are independently poor writers. Any user can take an article and improve its structure and grammer, but users are often more excited about writing new material. Below is an excerpt from the Morgan article:

It has often been claimed that Morgan invented the first “gas mask”, however, the first gas mask was invented by Scottish chemist John Stenhouse in 1854. A precursor to the “gas mask” had been invented by Lewis Haslett in 1847 and granted US Patent no. 6529 in 1859. Numerous other inventors, including, Charles Anthony Deane (1823), John Tyndall (1871), Samuel Barton (1874), George Neally (1877), Henry Fleuss (1878), before Morgan’s invention that was patented in 1914 (US Patent numbers 1090936 and 1113675), but does not diminish Morgan’s heroism in using his mask to rescue the men trapped in the tunnel explosion, which was undertaken at considerable personal risk.

Some claim that Morgan did not invent the first “gas mask”, however, those references are usually in reference to the “respirator.” Morgan invented the safety hood and later revised it, which was used to save trapped workers in the Lake Erie Crib Disaster of 1917. His safety hood eventually evolved to become a type of gas mask.

Wikipedia, “Garrett A. Morgan.”

I’ll leave finding the grammatical errors as an exercise to the reader, but it’s worth noticing that both paragraphs begin similarly but seem to be written without a clear awareness of each other. The writing does not flow, a common problem on Wikipedia. It’s also worth noticing, though, that the excerpt is not particularly hard to understand. It communicates sufficiently without doing so elegantly or grammatically. Wikipedia is a bad place to learn about writing style, but poor writing detracts only a little from its purpose as an encyclopedia.

Wikipedia should be looked at by educators as more than just a nuisance or a free encyclopedia. It's a potentially complicated tool, but one worth grappling with. I’ll close with the perspective of the researcher danah boyd, who studies relationships between youth and the internet:

If educators would shift their thinking about Wikipedia, so much critical thinking could take place. The key value of Wikipedia is its transparency. You can understand how a page is constructed, who is invested, what their other investments are. You can see when people disagree about content and how, in the discussion, the disagreement was resolved. None of our traditional print media make such information available. Understanding Wikipedia means knowing how to:

- Understand the assembly of data and information into publications

- Interpret knowledge

- Question purported truths and vet sources

- Analyze apparent contradictions in facts

- Productively contribute to the large body of collective knowledge

danah boyd, “Information Access in a Networked World,”

talk presented to Pearson Publishing, November 2, 2007.

For further reading, I recommend the articles linked from my citations above, as well as danah boyd’s small bookmark collection on Wikipedia.